Seminar Blogs

“Archiving Dance: The Irreducibility of Skill and Dynamism” – Danny Steur

Indulge me, very briefly, to share something about myself: I am not a dancer. Far from it, in fact; I am not a sportsy person at all, though I try to keep moving during a pandemic that has severely limited our options to go outside and move about the world. It seems best, in some ways, to stay put, keep inside, and wait out this whole ordeal so as not to inadvertently infect others or contract a certain virus myself. So, with all this, with or without pandemic: I greatly admire dancers, and the notion that dance is itself a form of knowledge seems completely logical – I do not know how to dance. James Leach writes about the effort, over recent decades, to recognize contemporary dance practices as a form of knowledge, though he contends that this occurs in a particular context: in order to appease a global political and economic, neoliberal order wherein ‘knowledge’ has been narrowly defined as crucial to (economic) prosperity and as a currency needed to maintain knowledge societies (2017, 141). Hence, knowledge needs to “appear in a certain form,” which tends to influence the practices concerned through a “subtle reshaping from the inside” (Leach 2017, 142).

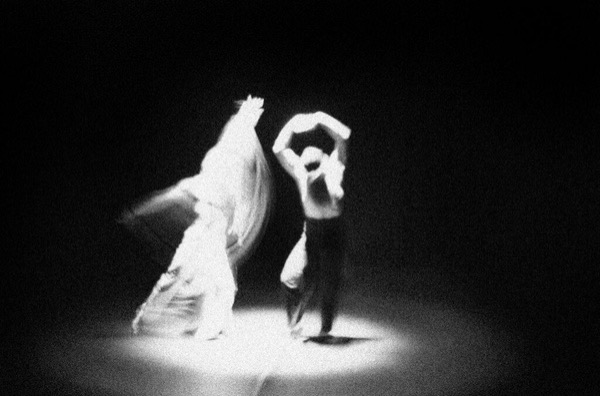

Besides this change from inside, a fear that I could see arising from this aim of capturing dance and recording, conserving and expressing it (archiving it, in other words) through representationalist, logocentric paradigms (Karreman 2017, 61) is that it instills a certain rigidity in their reproduction – thereby undoing a certain dynamism that has historically characterized dance. Diana Taylor famously distinguished between the archive, text-based epistemic knowledge practices, and the repertoire, the performative paradigm (with performance as “embodied practice and episteme”) of dynamic cultural practices of knowledge transfer in pre-colonial Latin American societies (2003, 17, 20). The repertoire “both keeps and transforms choreographies of meaning,” as the actions of the repertoire continually change over time (though its meanings might remain stable) (Taylor 2003, 20). It should be noted that the archiving practices discussed thus far relate to contemporary western dance practices, which I do not intend to compare or equate with the historical practices in the Americas. Nevertheless, Taylor’s comments insightfully characterize a quality of dance, and illustrate why the archiving of dance might come with anxieties about the practice losing its dynamism. To assuage that concern a bit Tim Ingold’s remarks on the irreducibility of skill seem helpful: while “narratives of use are converted by technology into algorithmic structures, these structures are themselves put to use within the ongoing activities of inhabitants, [they are] reincorporated into the field of effective action within which all life is lived” (2011, 62). New skills arise with the technologies aimed at preserving dance as knowledge, that dancers can integrate into their practices and doings. And in the context of a neoliberal reduction of dance to knowledge according to the money-form, these newly emergent skills can continue to subvert and escape the grasp of dance’s capture.

How to capture dance? Is it even possible to ‘capture’ movement through still means?

References:

- Ingold, Tim. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. London: Routledge.

- Karreman, Laura. 2017. “The Motion Capture Imaginary: Digital Renderings of Dance Knowledge.” PhD Dissertation, Ghent: Ghent University.

- Leach, James. 2017. “Making Knowledge from Movement: Some notes on the contextual impetus to transmit knowledge from dance.” In Transmission in Motion: The Technologizing of Dance, edited by Maaike Bleeker, 141-154. London: Routledge.

- Taylor, Diana. 2003. The Archive and the Repertoire: Cultural Memory and Performance in the Americas. Durham: Duke University Press.