Documentation

[Recap] TiM Seminar 2022-23 “The Medium is a Medium — Intersecting Technology and Spirituality in a More-than-human World” – Evelyn Wan (UU)

by Pauline Munnich

In the session “The Medium is a Medium” Evelyn Wan explored the intersection between technology and spirituality, reflecting on how intertwined the more-than-human world and technology have been throughout history.

Dali

Wan started by showing a video about an AI experience created by the Salvador Dali Museum in Florida, where AI technology was employed to create a deep fake Dali based on archival footage of the painter. Visitors of the museum are able to interact with the AI, who not only functioned as a tour guide to his own works but also was able to take selfies.

At the end of the video, Dali claims that “I do not believe in my death, do you?” insinuating that the painter is being preserved by the AI. Wan pointed out that despite believing in her own biological death, she is aware that she will continue to exist as a form of data for big data machinery to be used and processed so long as electricity exists.

Big tech and social media are aware of the value of death data as well, partly employing it to defy final death, and partly to seek ways to monetize grief. These death profiles will only continue to grow in number, ultimately outnumbering the profiles of those alive, with their data stored to be used.

Examples of monetizing grief

To exemplify how these companies monetize grief, Wan took us through several examples. The first example Wan presented was Replica, a chatbot originally designed by its creator to deal with the passing of a friend. The chatbot, through gathering data from private messages, is able to mimic the user’s personality and mannerisms. Through this, it is believed that it will be easier to form an empathetic bond. Simultaneously, over time, the chatbot could potentially become a digital version of the user, a version with which your loved ones can interact after you pass.

The second example Wan presented was the Metaverse company Sonmium Space. The company offers a Live Forever mode, allowing users to preserve themselves as avatars by permitting the capturing of speech and movement data. The company trains their avatars using the data, creating digital doubles that will continue to exist in the metaverse.

The last example Wan provided was Hereafter AI, a service that enables users to construct profiles with recorded memories for future generations to interact with, functioning much like an augmented version of a photo album. In contrast to the previous examples, Hereafter AI gives the user more agency on how they are preserved by the AI.

Legacy AI

These examples are what Wan described as Legacy AI. Legacy AI, through various ways, attempts to both preserve data as well as move beyond biological death. However, Wan stressed that this is not a recent development, but has been around for much longer which will be explored throughout this lecture, taking us through the history of immortality and technology.

Wan illustrated, by drawing on John Durham Peter’s work in Speaking into the Air (2000), that all mediated communication functions as communication with the dead as it can store, to a certain extent, “phantasms of the living”, which remain accessible after death.

Consequentially, Peter points out that throughout the history of communication media: “The two key existential facts about modern media are these: the ease with which the living may mingle with the communicable traces of the dead, and the difficulty of distinguishing communication at a distance from communication with the dead.”

To illustrate this point, Wan referred to two particular examples: the invention of the phonograph by Thomas Edison in the 1870s and the naming of mediumship as spiritual telegraph taking place around the same time. These two examples belong to two ways of looking at the equation around practices around death and technology. One goes from technology to practices around death and the other goes from practices around death to technology.

Edison’s Phonograph

The first historical example Wan focused on is the phonograph invented by Thomas Edison. The phonograph consists of a cylinder and two needles, one that through engravings records vibrations of the voice, and one that plays the recording back. As a result, the phonograph became the first machine able to play a disembodied voice, allowing for voices to be preserved even after death as communicable traces of the dead.

Furthermore, Wan illustrated how the phonograph was extensively used at funerals. One account, for instance, details the funeral of Revered Henry Slade in 1905 in New York, where he delivered his own eulogy that had been recorded shortly before his passing. Many funerals would play recordings of the deceased, having them either address their eulogy or have them sing.

The phonograph ultimately became so popular at funerals that in 1907, Elisabeth Haupoff patented the phonograph hearse, fashioning the coffin-bearing vehicle with a phonograph and two large horns from which music could be played. The departed, their family or others could choose what would play as the hearse traversed through the city.

Thus, what counted as spirit communication and as mediated communication was not clear-cut, leading to the beginnings of Spiritualism in the late 19th and 20th centuries. People believed that through these media they could communicate with the deceased. Even Edison himself believed in this, drawing up plans for a machine that allowed people to talk to the dead, though the machine was never physically created.

Hence, spiritualism and the sciences at the time were incredibly intertwined, with societies being created to specifically study supernatural phenomena and find ways to communicate with the beyond. The inventions of technology, therefore, were in line with these explorations due to the belief that technologies allowed for communication with spirits.

The naming of the mediumship as spiritual telegraph

Wan continued, showing how communicating with the dead oftentimes became compared to technology and related to communication at a distance.

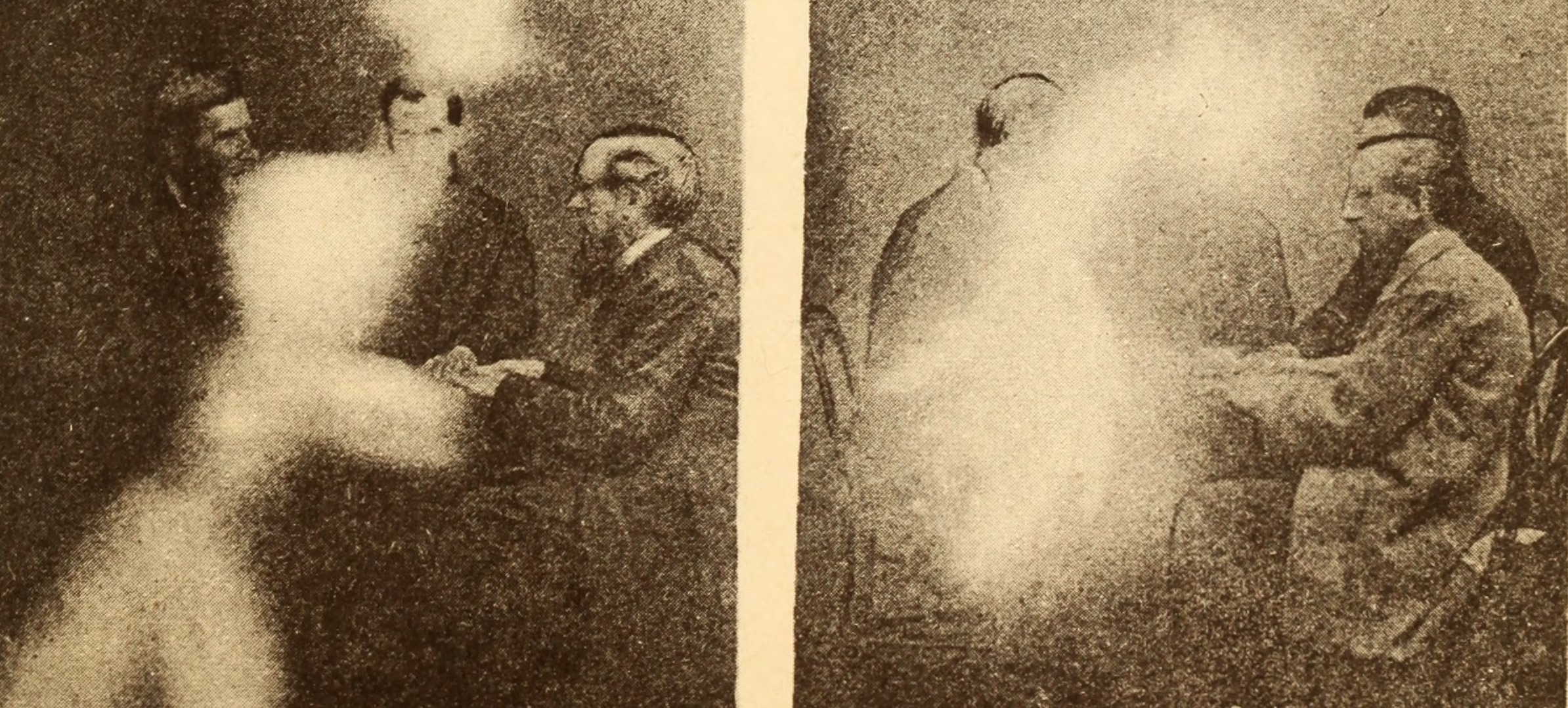

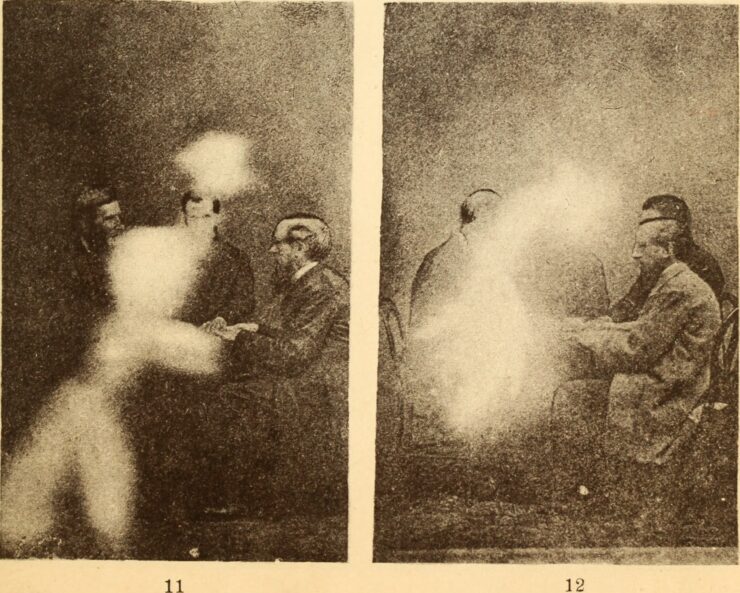

Tracing spiritualism back to the Fox sisters from New York, Wan explained how the sisters started to communicate with the spirits of their house in 1848 through patterned knocking. Eventually, this communication led to the sisters finding a body in their house, resulting in their fame and many travelling to their house to take part in these communications. As the sisters developed their techniques, connecting the knock to letters of the alphabet, morse code had just been invented, adding to the belief people could communicate through rhythmic codes over great distances. Eventually, the eldest sister decided to offer public performances of their seances, turning it into a form of entertainment with these communication types being known as spiritual telegraph.

At the same time, many technological objects were invented specifically to aid in spirit communication. One of these was the spiritual dial, where the user could direct the dial at a letter and the spirit would knock when it was the correct one. Ultimately, this led to the prototypical typewriter. Eventually, typewriters were also used in seances for spirits to type out their messages. Many believed mediums could not write these messages as they held their seances in the dark.

Wan explained, however, that it has never been truly confirmed whether these seances were fraudulent. At some point, two of the sisters claimed that their seances were not real but that they had trained their toes to knock and had become good at reading faces to get the correct answer. Yet, one of the sisters restated they had not been. It, additionally, had been rumoured that the sisters had come out as frauds in order to be paid by participating in experiments that would prove their fraudulence and both had been in desperate need of money. At the time, debunking mediums was quite popular, with even magicians such as Henry Nova detailing in clippings how popular techniques used by mediums could be achieved through physically training the body.

That being said, Wan emphasized that it is less about whether seances were fraudulent and more about the imagination around communication and the seances’ importance in offering a way to mourn in a time when deaths were frequent. Quoting Sconce in Haunted Media (2000), Wan underlined that, “In an era when the technology of the telegraph physically linked states and nations, the concept of telegraphy made possible a fantastic splitting of mind and body in the cultural imagination, demonstrating that electronic presence, whether imagines at the dawn of the telegraphic age or at the threshold of virtual reality, has always been more a cultural fantasy than a technological property.”

A Séance Performance

Wan then moved on to explore these cultural fantasies of spiritualism and technologies further, looking back at older themes. To do so, Wan invited us all to partake in a séance performance. She asks us to close our eyes and become aware of the technologies in our surroundings, imploring us to feel the data and signals that pass through our bodies. Wan then asked us to pay attention to the three names projected on the screen, Alan Turing, James Anderson and Teledo, asking us to focus on the name that we recognize.

Alan Turing

The name that ultimately comes out on top is Alan Turing. Turing famously devised a test, drawing inspiration from an old game that has often been compared to séance performances. In this game, a man and a woman sit behind a curtain with a player asking questions to which both provide written answers. The goal of the game was for the player to determine what answer belonged to whom. Turing refashioned the game to determine whether a computer was intelligent, replacing one person with a computer to observe whether it could pass as a human.

Similarly to the séance, where the medium functions as the player asking the spirit to verify its identity on the other side of the veil, both the Turing test and the medium are similarly structured and approach information and identity as being identical. Both assume that based on the transferred information, someone’s intelligence could be identified without them being bodily present.

Wan then reflected on the example of Dali, illustrating that, similarly to the Turing test and séance, we see no difference between Dali the AI and Dali who died. Still, Dali is not completely brought back from the dead and is merely an information exchange, as we are reminded that Dali the AI has its limitations. Yet, we still enjoy this experience much like people enjoyed seances. Similarly, AI becomes accessible to us through technological mediums, existing on an immaterial plane, echoing the Spiritualists’ spirits.

Thus, AI draws on the imagination of those who interact with it. Wan argued that what matters most when it comes to the Turing test, is our imagination about life beyond death and life behind the screen. To put it differently, technology is what we imagine it to be. Wan, therefore, pointed out how the Turing test explains how AI becomes a way for us to access a realm beyond death through our imagination, much like seances used to do.

James Anderson

The next name that Wan focussed on is James Anderson in order to explore whether we can view AI as a form of popular entertainment and what parts of Victorian history seances performed and concealed. To do this, Wan drew our attention to a séance taking place on the Great Eastern in 1865, a boat that had set out to lay the Trans-Atlantic telegraph cable. The first attempt had massively failed, with the attempt in 1865 being the second attempt which ultimately led to success.

Wan started out trying to retrace who had been aboard the ship. To do so, she attempted her own séance with the captain, but first, she sets the scene by showing imagines of the ship painted by Henry Clifford, who worked aboard the ship as an engineer. Wan described how during her research, she found a clipping on Captain Anderson’s séance, held before an audience, but could not seem to find who he had attempted to contact or what for. Thus, as the archive became a dead-end, Wan tried to contact Anderson through other means, asking GPT multiple times to describe the event. Although the answers changed, with GPT ultimately regarding it as a legendry tale, it still could not provide any answers, only able to construct memories based on existing texts which already lacked the needed information.

Wan explained how GPT recycles existing texts, using them to predict what could potentially come next based on these sources, describing this as a form of communicating with dead media. AI such as GPT continuously implore these data traces, extracting data beyond death, which David Bering Porter refers to as undead labour or zombie media. As long as the digital realm exists, data of that and those who have died will remain to be extracted and used. Similarly, the voice of GPT functions as a digital phantom, being a voice that belongs to no one and is generated based on algorithmic data. This voice, to put it differently, can be seen as the medium of working with the undead.

Teledo Cablistrius

Still, the question of who Anderson contacted has not been answered. Instead, Wan stumbled on a book containing a name, belonging not to a who but an it, a cable worm. Otherwise named shipworms, these Teledo worms appeared throughout history. One account by Dutch dike inspectors detailed how they could be found eating away at wooden dikes, risking for them to break during storms, becoming a real epidemic.

Wan, to sketch out the imagination of these shipworms as monsters, provided us with an image constructed from an AI image generator. Nevertheless, Wan pondered whether these worms truly were the monsters of the sea as they bear a connection to European colonialism where they resided in the wooden structures of ships, docks and dikes. Though it is not known where exactly these shipworms originated from, it is assumed that they travelled on ships departing from the Southeast Asian colonies.

Ships were not the only thing the worms attacked, however, they also feasted on the telegraph cables as they were insulated with Gutta Percha which allowed for the cables to survive underwater. Both the Teledo worms and the Gutta Percha tree originated from the Maley Peninsula where it was its main food source. When the British discovered that Gutta Percha preserved the cables, they had the enslaved harvest the trees. This was a hazardous job, as the trees were difficult to access, being located in tropical forests. Due to these conditions, many of the enslaved were injured or killed. Their lives were seen as expendable in the eyes of the colonizers.

Moreover, the tree ultimately went extinct to the vast amount that was needed, with it being coined as the first victim of the ecological crisis. By the early 1880s, the jungles of Malaysia and Singapore had been completely stripped with the ban on harvesting in 1883 having no effect.

These forms of colonial exploitation and destruction still persist in the infrastructure of technology today. Consequentially, there are many ghosts of AI, spanning from the exploitation of human labour to the exploitation of non-human animals and materials.

Afterword: of mediums, machines and ghosts

To end the seminar, Wan presented three statements to draw the lecture together: the medium is a medium, digital culture is necropolitical and all AI is legacy AI.

the medium is the medium: Colonialism has spurred spiritualism with the many deaths occurring due to colonial expansion and telegraph construction. Wan briefly described the example of William Crooke, a chemist who became obsessed with Spiritualism after his brother died of Yellow Fever aboard a cable-laying ship that belonged to the India-rubber Gutta-Percha and Telegraph Work Company. As Wan sought to underline during the lecture, there is a link between spiritual imagination and technology, where the telegraph as a medium gave entry to the world of mediumship and spirituality whilst allowing for its creation to be linked with the spiritual imagination. Hence, it is not the séance performance or the technology that completes the experience of the media, but instead, it is our own imaginations.

Digital culture is necropolitical: In the beginning Wan explored dead labour in the form of data used in AI, linking this to the undead labour of slaves embodied in the telegraph cables. Wan drew from Mbembe, illustrating that these cables belong to necropower. The telegraph spurred on the imagination of the Victorians, yet what is obscured by the great entertainment value of seances were the deaths that were not memorialized. Wan emphasized that there was no documentation to be found on how many had died in the construction and laying of the telegraph layers. Thus, the necropower of the telegraph system can not accurately be tallied. Yet, there is no shortage of accounts celebrating how glorious this feat was, calling it the eighth wonder of the world. In this lecture, Wan sought to explore how bio power and necropower could potentially be connected to AI, reflecting on what lives are commemorated, extracted or left to die.

All AI is Legacy AI: Lastly, Wan argued that all AI is legacy AI, drawn from data archives constructed from living or rather dead data. These processes of data extraction will continue even after biological death being quite valuable to AI. Historical data, in other words, holds infinite value, remaining valuable for algorithms as it allows for recombination and creative manipulation. Therefore, all AI is legacy AI, attempting to enter undead time. Taking it back to the example of Dali, Wan illustrated that Dali no longer is just a dead surrealist painter thanks to AI. Instead, he is a tour guide, an AI image generator and a style of a hallucinatory neural network as well.

Wan ended the lecture by asking some final questions in connection to the Turing test. If AI needs our imagination to fill in the gaps in order for us to think of it as intelligent much like how those before us used their imagination to fill in the gaps for the seances that we discussed earlier, how could we use our imagination differently, refusing the way we currently fill in the gap? Additionally, how could we reimagine the Turing Test as a séance that addresses the real ghosts embedded in technologies, part of the extraction and undead labour in the service of capitalism, to demand their justice?

Questions

There were quite a lot of questions after the lecture. Some of the attendees pondered the role of the materialization of the invisible through technology, functioning like a medium. Others asked about the fascination of extending life and how it could potentially neglect death. Another linked it to Capitalism and its mechanisms of selling desire. One of the attendees then pondered whether they would have to include a clause in their will in order not to be replicated as AI. Their second question revolved around who the true owner of data is and whether this reflects data colonialism. Another attendee remarked that in regards to overcoming death, the lecture had taken a human perspective, wondering what it meant for certain data formats whilst technology develops so incredibly fast. Someone else noted that AI was merely a representation of the real world whilst the real person and their biological consciousness would pass, so do we truly have a need for AI; why do we want/need a substitute? One of the attendees wondered how the dramaturgy of the séance relates to algorithmic culture, pointing at how it shits from the medium as a person towards generating possibilities. In connection to Wan’s argument about seances not really mattering compared to the imagination for it to be real, the attendee wondered what role trust played in these experiences.