News

[Recap] TiM Seminar 2022-23 “Cultural Dreams of Datafied Bodies in Contemporary Performance” – Laura Karreman (UU)

by Pauline Munnich

In the session “Cultural Dreams of Datafied Bodies in Contemporary Performance” Laura Karreman discusses recent artworks arising from the cultural imagination of bodies in movement and motion capture. She does this by focusing on dance, illustrating the link between movement and the motion capture imaginary, drawing on her book Embodied Computation (preliminary title) that she is currently developing and on previous research.

1. The Imaginary

The Imaginary is a notion that has popped up in different fields, but what exactly does it mean? Karreman refers to imagination as creative thinking. To explore the connection between the imaginary and technology she proposes two questions that together form a critical pair. Firstly, what are today’s sociotechnical imaginaries and how do they manifest themselves? Secondly, what potential do we see for creative imagination to change and transform them?

The imaginary as a form of creative thinking about technology and its potential is not a new phenomenon. As Adrienne Mayor (2018) in the book Gods and Robots: The Ancient Quest for Artificial Life illustrates, there already seems to be thought experiments on what technology could potentially become in Greek myth. As Mayor describes “such myths can be considered as ‘cultural dreams, ancient thought experiments, “what-if” scenarios set in an alternate world of possibilities, an imaginary space where technology was advanced to prodigious degrees” (2018: 2) Thus, these myths function as ancient thought experiments or what-if scenarios of the possibilities of technology.

However, these imaginaries are quite paradoxical. On the one hand, they are mental constructs without any tangible form, but on the other hand, they do have an impact on how technologies develop, making these imaginaries eventually tangible. In other words, there are particular ways that we think about technology which, in turn, impact actual technologies and how we view them.

Hence, Karreman notes “If we want to understand a technological phenomenon as a cultural phenomenon, it pays to see if we can figure out what ideas, intentions, fantasies have dreamed it into being.”

2. Note that all of this is rather strange

Image 1: Dog on a leash

To exemplify the point, that all of this is rather strange, Karreman introduces a picture of a dog on a leash. The dog is wearing a suit with a lot of markers on it and on its fur, additional markers can be seen, placed in an asymmetrical manner. Although out of focus, the background shows a screen, camera and green walls, in other words, a studio recording motion capture. Despite being a strange image, the markers and suit serve a purpose, being able to reflect an infrared light that then is captured and translated into data to ultimately record the movement of the dog and reconstruct it as a 3D model.

Still, the picture by being rather strange puts our judgement on hold as we try to make sense of it. We cannot help but ask, “How did this dog get into this situation?”

3. The horse and nothing but the horse

To understand how the dog ended up in this position, Karreman takes us back in time, bringing up a classic example of motion capture. She shows The Horse in Motion by Eadweard Muybridge, a series of photographs depicting a horse running. Through a sequential series of photographs, Muybridge is able to capture the movement of the horse, breaking up the movement into separate photographs.

Image 2: Muybridge The Horse in Motion

Still, it begs to ask the question, why did these pictures get taken? Governor Stanford, the man responsible for the commissioning of the photographs, made a bet whether or not a horse would lift off the ground during a gallop. However, it was quite difficult to prove whether or not he was as there is no way to see this with the naked eye due to the movement being too quick. Thus, Governor Stanford approached Muybridge who at the time was experimenting with the exposure time of photographs. Stanford had always been quite obsessed with motion, approaching it as a mystery to be solved, and this time, with the help of Muybridge, he sought to demystify the movement of the horse.

Nevertheless, it was easier said than done. To do so, they had to design a set-up that would work out in the field where the horse could run at its full speed. Muybridge, as a result, ordered numerous white sheets that he put on poles and on the ground. He did this to ensure that there would be enough light reflected to take the pictures. The only downside of this was that the set-up was incredibly bright. Consequentially, the horse needed to be trained to move over the blinding terrain. In the end, Muybridge succeeded and the experiment brought moving bodies, such as the horse, into visibility, making Governor Stanford win his bet.

Image 3: Marey chronophotography

Muybridge was not the only photographer seeking to capture movement, another photographer, Etienne-Jules Marey, sought to do so as well, although in a different manner. Marey practised chronophotography, recording several phases of movement onto one photographic surface to portray the flow of movement.

These examples of motion capture imaginary although different in their methods of depicting movement, do share some key elements:

- Picturing the invisible:

Both Marey and Muybridge seek to render something visible that had never been seen before. - Fixation and re-iterability:

Their photographs seek to fix movement so that we can look at it repeatedly. - Visualism:

Seeing is believing. If we see it in the image then it’s truth. - Abstraction of movement…:

It can already be seen in both images, both photographers cut up the movement to portray it. They focus on showing patterns of movement. - …through deliberate strategies of staging:

Both photographers need to create a specific setting in order for the pictures to be taken (e.g. teaching the horse to run over sheets, ensuring the setting reflects enough light, etc.).

These elements create an understanding of what movement is and how it is to be captured by technology.

4. How to save dance from its ephemerality?

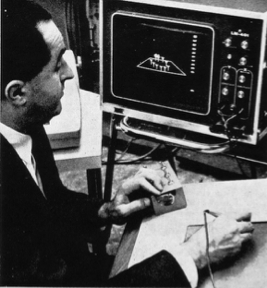

Image 4: Noll and computer dance notation

In the 1960s Michael Noll experimented with early computer graphics. He was interested not only in computers but also in dance, seeking to explore how computers can help/change dance. Noll felt that it could help in particular with dance notation, one of the systems used to transmit choreography, as one of the problems with dance notation was that it took a long time to create.

Noll, thus, initially treated the computer as a typewriter, believing it could aid in the writing of such dance notations. He designed a set of stick figures that the choreographer could manipulate in order to create a routine. Not only would this make notation easier, Noll believed it would even allow the choreographer to create choreography without the dancers present. The dancers, instead, would be able to come in later once the choreographer already had designed the choreography, saving time.

This was not the only benefit that Noll saw with this new form of notation; there was also the possibility that the computer could record dance. By dancing in a dimly lit room with white markers and by recording the dance from different angles, the dance could be translated into a 3D model.

Thus, as the motion capture imaginary evolved and two new key elements can be added to the already aforementioned list:

- Picturing the invisible:

Both Marey and Muybridge seek to render something visible that had never been seen before. - Fixation and re-iterability:

Their photographs seek to fix movement so that we can look at it repeatedly. - Visualism:

Seeing is believing. If we see it in the image then it’s truth. - Abstraction of movement…:

It can already be seen in both images, both photographers cut up the movement to portray it. They focus on showing patterns of movement. - …through deliberate strategies of staging:

Both photographers need to create a specific setting in order for the pictures to be taken (e.g. teaching the horse to run over sheets, ensuring the setting reflects enough light, etc.). - Saviour complex:

Saving movement from its ephemerality. - Three-dimensional access:

By creating an image of movement through different camera angles.

6. The dancing-drawing body

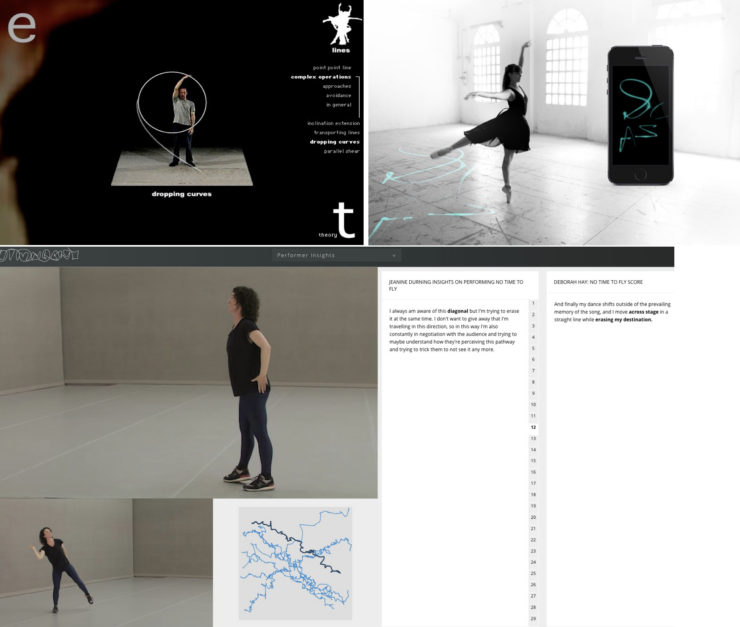

Image 5: Up Left Image: William Forsythe’s Improvisation Technologies, Up Right Image: Lesia Trubat’s E-traces, Bottom image: No Time to Fly performed by Jeanine Durning

There are many different examples of what the dancing-drawing body can be. Sometimes, as in the case of William Forsythe’s Improvisation Technologies, the dancing-drawing body is traces added at a later stage to a video or image to visualize movement. Other examples of dancing-drawing bodies, such as Lesia Trubat’s E-traces, are the traces recorded from devices where movement is used to create these traces. Another example is a type of recorded trace created by a set of instructions such as the artwork No Time to Fly performed by Jeanine Durning.

These dancing-drawing bodies come from the need to understand data from moving bodies. When we move through space we leave behind a trace. Motion caption data can be very difficult to interpret, consisting of three columns with numbers that we cannot process as humans but only can be accessed after rendering. There is, in other words, a translation process of data where we need to find the rightness of the rendering to result in data that we can interpret. The dancing-drawing body offers one way of doing this, rendering the trace of movement visible and legible to us.

Hence, the dancing-drawing body can be seen as one of the key elements of the motion capture imaginary.

- Picturing the invisible:

Both Marey and Muybridge seek to render something visible that had never been seen before. - Fixation and re-iterability:

Their photographs seek to fix movement so that we can look at it repeatedly. - Visualism:

Seeing is believing. If we see it in the image then it’s truth. - Abstraction of movement…:

It can already be seen in both images, both photographers cut up the movement to portray it. They focus on showing patterns of movement. - …through deliberate strategies of staging:

Both photographers need to create a specific setting in order for the pictures to be taken (e.g. teaching the horse to run over sheets, ensuring the setting reflects enough light, etc.). - Saviour complex:

Saving movement from its ephemerality. - Three-dimensional access:

By creating an image of movement through different camera angles. - The dancing-drawing body

7. Acts of Holding Dance

This brings the session to the last example, the Erasmus+ staff mobility exchange programme that took place at the Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne. The exchange programme consisted of different motion capture projects. One of these projects, the Machine Movement Lab by Petra Gemeinboeck, for example, consisted of dancers teaching robots movement so that the cubes started to move in a human-like way.

Image 6: Breaking Wendy Yu

Another project, Acts of Holding Dance by Wendy Yu, consisted of art projections on high-rise buildings where the limbs of the dancers are stretched and elongated. In her project Breaking she worked specifically with break-dancers, each having a local style to the city where she sought to project her work. In her work, she lifted them from the ground stretching out parts of the body that touched the ground. The images created referenced moments of dance notation and motion capture history as discussed during the session.

8. How to re-imagine the motion capture imaginary?

Karreman emphasizes that she does not necessarily have the solution for this, but that she does have some hints and ideas on how to re-imagine the motion capture imaginary. She proposes three points that should be kept in mind when trying to re-imagine the motion capture imaginary.

Firstly, we need to investigate more ways to articulate embodied knowledge about movement. Currently, motion capture misses a lot of information. One of the things it does not capture, for instance, is what goes on inside bodies.

Secondly, we need to examine the ethical implications of the abstraction of motion data from human and non-human subjects. Motion capture is also about identity and identifying bodies. Moreover, it complicates the question of authorship of bodies and movement, is the one moving the author of the captured movement or the one in charge of the capturing?

Thirdly, we need to approach motion capture from a posthuman paradigm instead of an empiricist paradigm. There should be more attention to the co-creation and intra-action between motion capture and the body. Steph Hutchinson and Jogn McComick provide an example of what this could look like in their performance Emergence. Here Hutchinson dances in a motion-capture setting, creating a duet between them and the motion capture. The dance, to put it differently, is a co-creation between the dancer and the technology.

Lastly, we need to analyse motion capture as performance, understanding it as motion creation. As already seen with the picture of the dog, there is an aspect of staging to motion capture with animals being trained to behave in a certain way in a specific setting for the motion to be recorded. What we find through motion capture is directly connected to what we set up to find and therefore motion capture can be seen as a creative practice.

At the end of the session, several interesting questions and remarks were proposed by the audience. Some audience members, for example, pondered whether motion capture could put the distinction between the composer/choreographer genius and the dancer/performer into question, exploring together with others to whom that captured movement actually belonged. Another question discussed the question of authorship even further and connected it to datafication. Lastly, one of the audience members asked about the role of race in motion capture and its historical archive, pointing out that the jockey in Muybridge’s The Horse in Motion was a black rider.